[cs_content][cs_section bg_image=”https://annualreport2019.rtb.cgiar.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/fp3-top.png” parallax=”false” separator_top_type=”none” separator_top_height=”50px” separator_top_inset=”0px” separator_top_angle_point=”50″ separator_bottom_type=”none” separator_bottom_height=”50px” separator_bottom_inset=”0px” separator_bottom_angle_point=”50″ _order=”0″ _label=”Section 1″ style=”margin: -25px 0px 0px;padding: 0px;background-position: left top;background-size: 100%;”][cs_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”transparent” style=”margin: 0px auto;padding: 250px 0px 0px;”][cs_column fade=”false” fade_animation=”in” fade_animation_offset=”45px” fade_duration=”750″ type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0 0px 0px;”][x_custom_headline level=”h2″ looks_like=”h3″ accent=”false” class=”cs-ta-left” style=”color: rgb(80, 184, 77);margin-top: 0px;”]Smarter farming: using apps to diagnose crop health problems[/x_custom_headline][/cs_column][/cs_row][/cs_section][cs_element_section _id=”5″ ][cs_element_layout_row _id=”6″ ][cs_element_layout_column _id=”7″ ][cs_text]

New apps are now being tested with thousands of farmers in Africa, South Asia and the Andes to diagnose the pests and diseases of cassava, banana and potato crops. These decision tools can be used with a smartphone, and some also have a hand-held, printed version. Some apps use artificial intelligence, developed through machine learning, to recognize major disease symptoms and pest damage, and to give advice on controlling the pest. The printed charts use information provided by the farmer to help decide on specific management recommendations.

Information and communication technologies (ICT), such as apps, can help extensionists and farmers to produce food more efficiently, and to be more resilient in the face of risks, such as pests and diseases. The RTB team involving IITA, Bioversity International, CIAT and CIP are inspiring each other to create new apps and to improve recently developed ones to help farmers diagnose plant health problems and to decide on the best ways to manage them. There is an effort to make the apps interoperable and the data they collect easily shared. This will allow for a global tracking and monitoring system that will work in real-time and could make information collected by farmers, extensionists and scientists available to support decision making in the field and also at the policy level.

A team from Penn State University, CIP, IITA and RTB have won the Inspire Challenge Award (from the CGIAR Platform for Big Data in Agriculture) for their app called PlantVillage Nuru (Swahili for “light”). Nuru uses machine learning and Google’s open source TensorFlow software to recognize symptoms of leaf damage caused by diseases and pests. Nuru can recognize cassava brown streak disease (CBSD), cassava mosaic disease (CMD) and cassava green mite damage (CGM), as well as the healthy leaf condition.

[/cs_text][/cs_element_layout_column][/cs_element_layout_row][cs_element_layout_row _id=”9″ ][cs_element_layout_column _id=”10″ ][cs_element_icon _id=”11″ ][cs_element_quote _id=”12″ ][cs_element_icon _id=”13″ ][/cs_element_layout_column][/cs_element_layout_row][cs_element_layout_row _id=”14″ ][cs_element_layout_column _id=”15″ ][cs_text]

To use Nuru, you start up the app in your android phone, point the phone’s camera at a cassava leaf in the field, and Nuru will identify the condition in a matter of seconds. It’s like having a plant doctor in your pocket.

[/cs_text][/cs_element_layout_column][/cs_element_layout_row][cs_element_layout_row _id=”17″ ][cs_element_layout_column _id=”18″ ][cs_element_icon _id=”19″ ][cs_element_quote _id=”20″ ][cs_element_icon _id=”21″ ][/cs_element_layout_column][/cs_element_layout_row][cs_element_layout_row _id=”22″ ][cs_element_layout_column _id=”23″ ][cs_text]

Nuru has been downloaded from the Play Store more than 1,000 times and users have generated more than 16,000 reports from 60 countries—adding to the app’s database of images.

Self Help Africa, an NGO, is testing Nuru with 28,000 farmers in seven counties of Kenya. Nuru is still undergoing improvement, and its accuracy is much higher with severe symptoms than with mild ones. Making further improvements to the app is important, because farmers can manage disease better if they diagnose it early, spotting mild symptoms. Improved accuracy is a challenge, especially since viral disease symptoms can be difficult to distinguish, but Nuru is improving quickly. The RTB teams involved are working to extend the use of the app to potato and potentially other crops. In addition to Nuru, the teams are working on other decision support tools for farmers to diagnose plant health.

A new app called Tumaini (“hope” in Swahili) is used on a smartphone to diagnose major diseases of banana, including Xanthomonas wilt, Fusarium wilt and black Sigatoka. Farmers who have tested Tumaini in Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo, India, Benin, China and Uganda have found the app to be 90% accurate.

[/cs_text][/cs_element_layout_column][/cs_element_layout_row][cs_element_layout_row _id=”25″ ][cs_element_layout_column _id=”26″ ][cs_element_icon _id=”27″ ][cs_element_quote _id=”28″ ][cs_element_icon _id=”29″ ][/cs_element_layout_column][/cs_element_layout_row][cs_element_layout_row _id=”30″ ][cs_element_layout_column _id=”31″ ][cs_element_image _id=”32″ ][cs_text]

To make a diagnosis with Tumaini, you take a photo of the plant symptoms with your phone. The app saves your photo to improve future diagnoses. Tumaini gives the user management options, even without an internet connection.

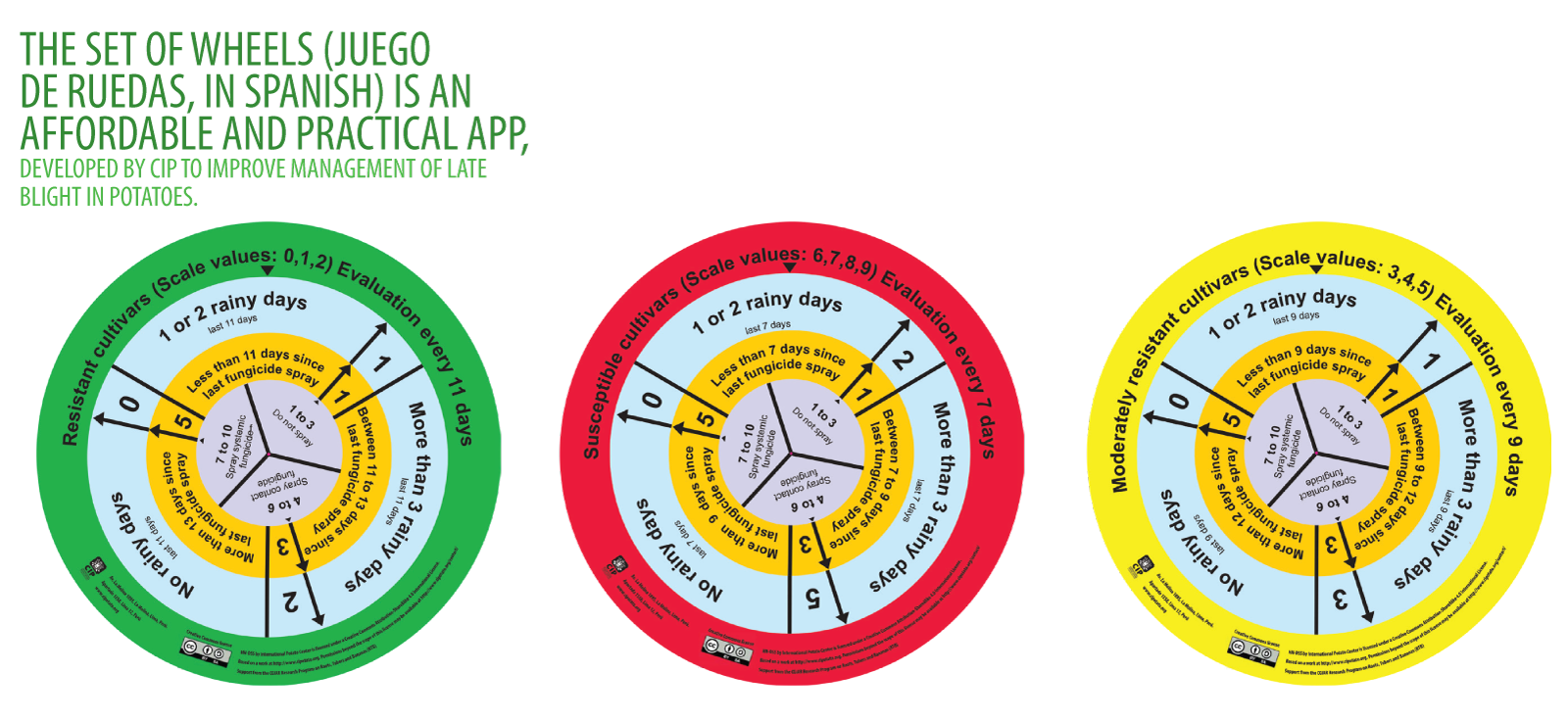

The Set of Wheels (Juego de Ruedas, in Spanish) is an affordable and practical app, developed by CIP improve management of late blight in potatoes. It helps farmers to decide when to spray fungicides and what to spray. There is also an offline version that includes a red cardboard wheel for potato varieties that are susceptible to late blight, a yellow wheel for moderately susceptible varieties, and a green wheel for resistant ones. Each wheel is a simple chart, which indicates whether to spray with a contact fungicide, a systemic fungicide, or to apply nothing, based on the frequency of recent rains and the time since the last fungicide application. The wheels help farmers use less fungicide, while effectively managing late blight. Farmers are now using it in Peru and Ecuador, with trials planned elsewhere.

[/cs_text][/cs_element_layout_column][/cs_element_layout_row][cs_element_layout_row _id=”34″ ][cs_element_layout_column _id=”35″ ][cs_element_icon _id=”36″ ][cs_element_quote _id=”37″ ][cs_element_icon _id=”38″ ][/cs_element_layout_column][/cs_element_layout_row][cs_element_layout_row _id=”39″ ][cs_element_layout_column _id=”40″ ][cs_text]

Diagnosing crop health problems and deciding how to manage them has always been one of a farmers’ biggest challenges. Recent advances in information and communication technology promise to help farmers make smarter decisions.

[/cs_text][cs_element_image _id=”42″ ][cs_element_text _id=”43″ ][/cs_element_layout_column][/cs_element_layout_row][/cs_element_section][cs_section bg_color=”transparent” parallax=”false” separator_top_type=”none” separator_top_height=”50px” separator_top_inset=”0px” separator_top_angle_point=”50″ separator_bottom_type=”none” separator_bottom_height=”50px” separator_bottom_inset=”0px” separator_bottom_angle_point=”50″ _label=”Section 2″ style=”margin: 0px;padding: 30px 0px 45px;background-size: 100%;background-position: top;”][cs_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” style=”margin: 0px auto;padding: 0px;”][cs_column fade=”false” fade_animation=”in” fade_animation_offset=”45px” fade_duration=”750″ type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0 0px 0px;”][x_share title=”SHARE THIS” share_title=”” facebook=”true” twitter=”true” google_plus=”false” linkedin=”true” pinterest=”false” reddit=”false” email=”true” email_subject=””][/cs_column][/cs_row][/cs_section][/cs_content][cs_content_seo]Smarter farming: using apps to diagnose crop health problems

New apps are now being tested with thousands of farmers in Africa, South Asia and the Andes to diagnose the pests and diseases of cassava, banana and potato crops. These decision tools can be used with a smartphone, and some also have a hand-held, printed version. Some apps use artificial intelligence, developed through machine learning, to recognize major disease symptoms and pest damage, and to give advice on controlling the pest. The printed charts use information provided by the farmer to help decide on specific management recommendations.

Information and communication technologies (ICT), such as apps, can help extensionists and farmers to produce food more efficiently, and to be more resilient in the face of risks, such as pests and diseases. The RTB team involving IITA, Bioversity International, CIAT and CIP are inspiring each other to create new apps and to improve recently developed ones to help farmers diagnose plant health problems and to decide on the best ways to manage them. There is an effort to make the apps interoperable and the data they collect easily shared. This will allow for a global tracking and monitoring system that will work in real-time and could make information collected by farmers, extensionists and scientists available to support decision making in the field and also at the policy level.

A team from Penn State University, CIP, IITA and RTB have won the Inspire Challenge Award (from the CGIAR Platform for Big Data in Agriculture) for their app called PlantVillage Nuru (Swahili for “light”). Nuru uses machine learning and Google’s open source TensorFlow software to recognize symptoms of leaf damage caused by diseases and pests. Nuru can recognize cassava brown streak disease (CBSD), cassava mosaic disease (CMD) and cassava green mite damage (CGM), as well as the healthy leaf condition.

Partnerships were really important in the development and piloting of this app, says James Legg, who is RTB’s FP3 leader, and this is where working with our flagship team has been so vital, as it fosters strong cooperation between CGIAR scientists, while also encouraging the development of new initiatives with external partners, such as Penn State.

To use Nuru, you start up the app in your android phone, point the phone’s camera at a cassava leaf in the field, and Nuru will identify the condition in a matter of seconds. It’s like having a plant doctor in your pocket.

You wave your phone over a specific leaf, and if it has a symptom, a box will pop up saying ‘you have this problem.’ When you get a diagnosis, you learn about the best management practices, explains Amanda Ramcharan, who was part of the Penn State team.

Nuru has been downloaded from the Play Store more than 1,000 times and users have generated more than 16,000 reports from 60 countries—adding to the app’s database of images.

Self Help Africa, an NGO, is testing Nuru with 28,000 farmers in seven counties of Kenya. Nuru is still undergoing improvement, and its accuracy is much higher with severe symptoms than with mild ones. Making further improvements to the app is important, because farmers can manage disease better if they diagnose it early, spotting mild symptoms. Improved accuracy is a challenge, especially since viral disease symptoms can be difficult to distinguish, but Nuru is improving quickly. The RTB teams involved are working to extend the use of the app to potato and potentially other crops. In addition to Nuru, the teams are working on other decision support tools for farmers to diagnose plant health.

A new app called Tumaini (“hope” in Swahili) is used on a smartphone to diagnose major diseases of banana, including Xanthomonas wilt, Fusarium wilt and black Sigatoka. Farmers who have tested Tumaini in Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo, India, Benin, China and Uganda have found the app to be 90% accurate.

The increasing popularity of smartphones and recent advances with digital imaging made possible by deep learning allow Tumaini to diagnose banana diseases, says Michael Selvaraj, who led the research team at Alliance Bioversity-CIAT.

To make a diagnosis with Tumaini, you take a photo of the plant symptoms with your phone. The app saves your photo to improve future diagnoses. Tumaini gives the user management options, even without an internet connection.

The Set of Wheels (Juego de Ruedas, in Spanish) is an affordable and practical app, developed by CIP improve management of late blight in potatoes. It helps farmers to decide when to spray fungicides and what to spray. There is also an offline version that includes a red cardboard wheel for potato varieties that are susceptible to late blight, a yellow wheel for moderately susceptible varieties, and a green wheel for resistant ones. Each wheel is a simple chart, which indicates whether to spray with a contact fungicide, a systemic fungicide, or to apply nothing, based on the frequency of recent rains and the time since the last fungicide application. The wheels help farmers use less fungicide, while effectively managing late blight. Farmers are now using it in Peru and Ecuador, with trials planned elsewhere.

The good performance of the Juego de Ruedas for late blight management indicates the value of integrating some of the factors driving disease severity in the decision-making process of using fungicides. This is especially important in areas with poor access to internet and weather data, says plant pathologist Jorge Andrade-Piedra at CIP.

Diagnosing crop health problems and deciding how to manage them has always been one of a farmers’ biggest challenges. Recent advances in information and communication technology promise to help farmers make smarter decisions.

Smartphone apps allow farmers to crowdsource information for more timely interventions. E. Yvonne

SHARE THIS

[/cs_content_seo]

[/cs_content_seo]