[cs_content][cs_section bg_image=”https://annualreport2019.rtb.cgiar.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/fp3-top.png” parallax=”false” separator_top_type=”none” separator_top_height=”50px” separator_top_inset=”0px” separator_top_angle_point=”50″ separator_bottom_type=”none” separator_bottom_height=”50px” separator_bottom_inset=”0px” separator_bottom_angle_point=”50″ _order=”0″ _label=”Section 1″ style=”margin: -25px 0px 0px;padding: 0px;background-position: left top;background-size: 100%;”][cs_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”transparent” style=”margin: 0px auto;padding: 250px 0px 0px;”][cs_column fade=”false” fade_animation=”in” fade_animation_offset=”45px” fade_duration=”750″ type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0 0px 0px;”][x_custom_headline level=”h2″ looks_like=”h3″ accent=”false” class=”cs-ta-left” style=”color: rgb(80, 184, 77);margin-top: 0px;”]Potatoes and legumes: better together[/x_custom_headline][/cs_column][/cs_row][/cs_section][cs_element_section _id=”5″ ][cs_element_layout_row _id=”6″ ][cs_element_layout_column _id=”7″ ][cs_element_image _id=”8″ ][cs_text]

Legumes can be intercropped with potatoes to help manage soil erosion. In addition, a legume intercrop boosts the overall productivity of the land, while helping to improve soil moisture and soil fertility.

In East Africa, potatoes are an important crop for consumers and for highland farmers, helping to improve the livelihoods of rural families. Potato fields usually depend on intensive tillage, contributing to erosion on fragile soils, particularly on slopes. Farmers are also starting to plant potatoes at somewhat lower altitudes where heat and drought are problems. Here, low yields and erosion are exacerbated by the warmer, dryer climate, and by more erratic rainfall. Yet with a growing population, people need to use land more intensively and in a sustainable manner.

[/cs_text][cs_element_image _id=”10″ ][cs_text]

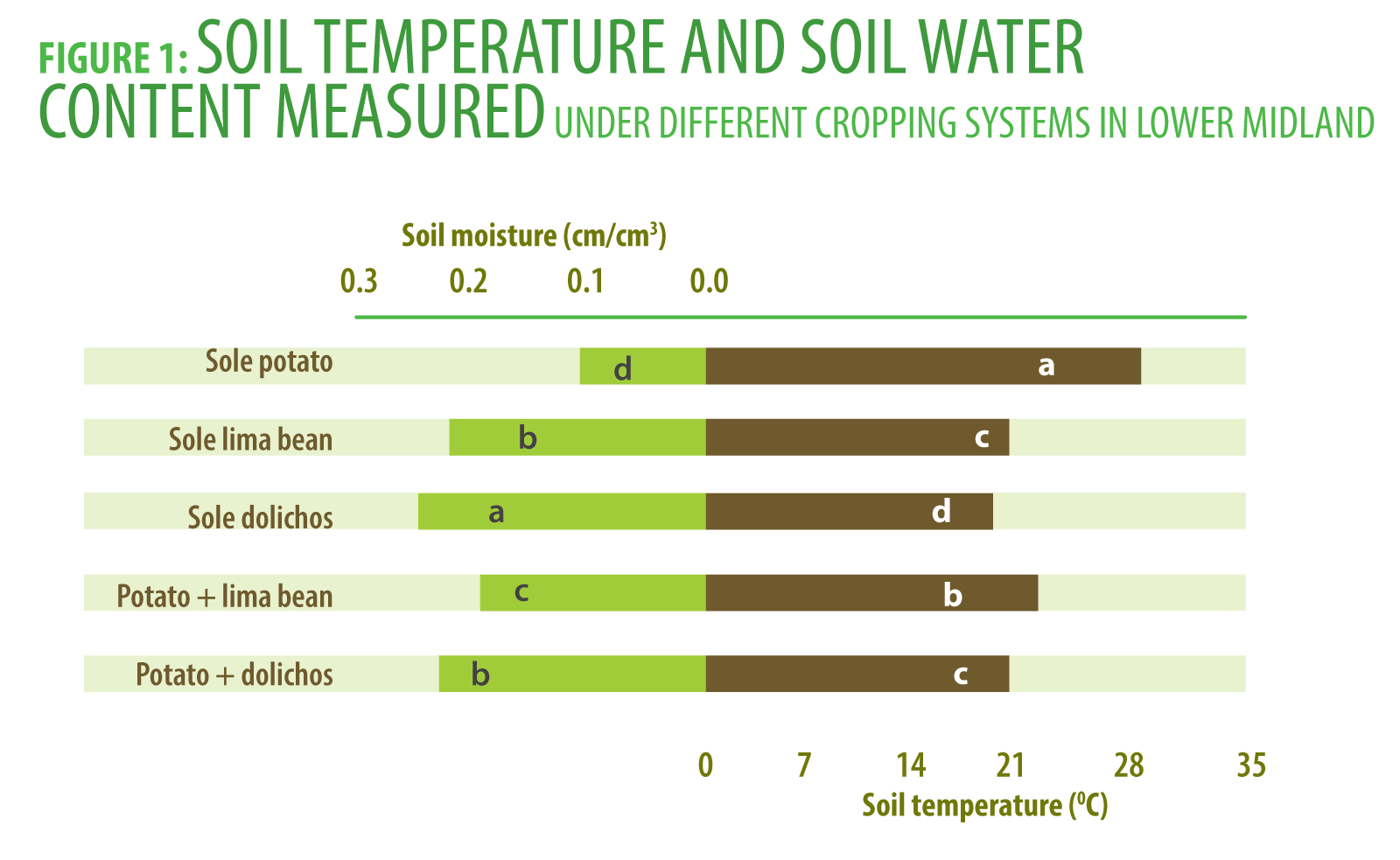

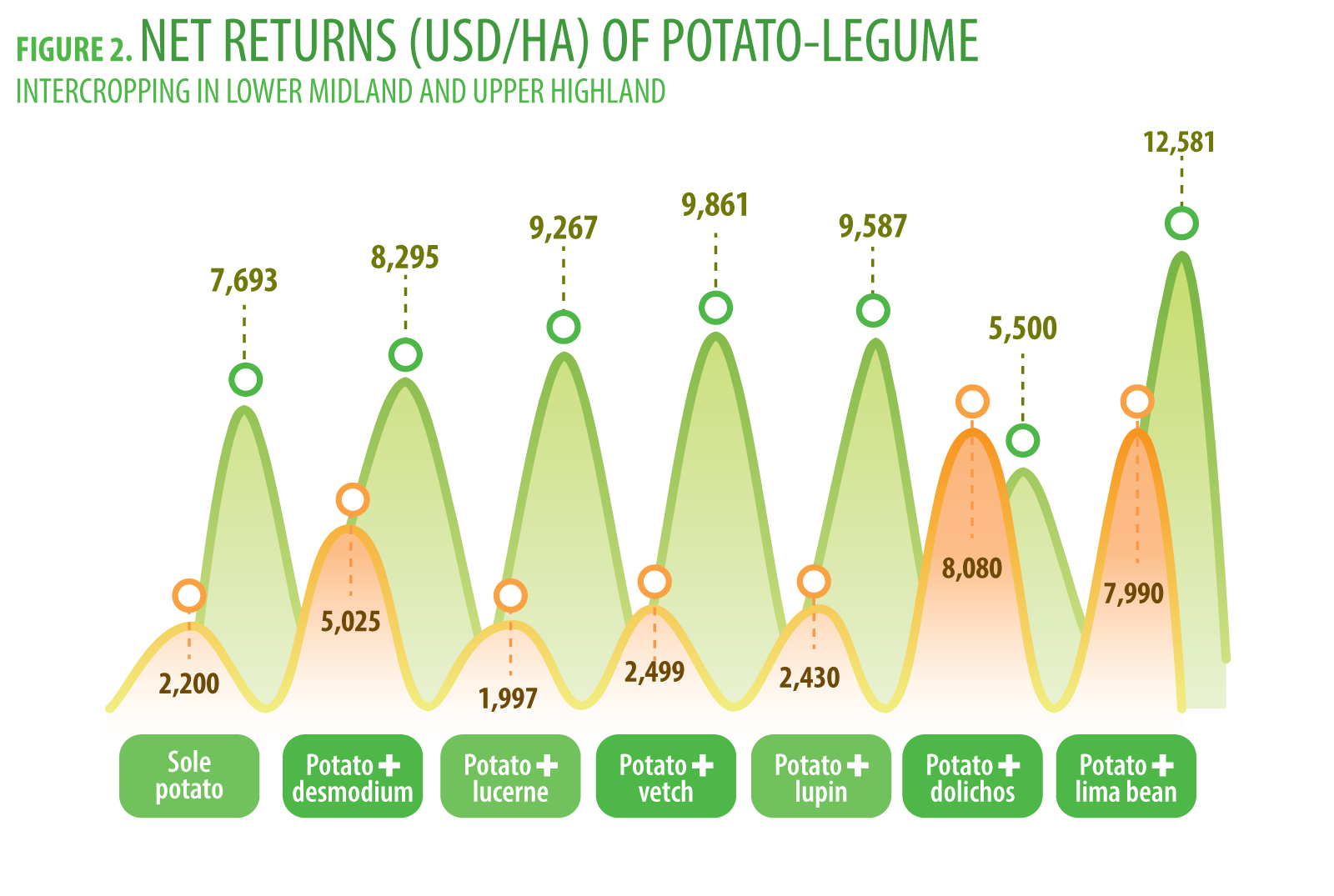

A CIP team is developing a practical solution to improve soil conservation in the East African highlands by intercropping potatoes with legumes. The legumes grow a thick canopy of leaves, which covers the soil, shading and cooling it, thus increasing soil moisture (see Figure 1). This helps the potato crop in warmer areas. When cropped on steeper land, the thick canopy reduces damage from hard rainfall and protects the soil from erosion caused by runoff. And by adding a legume crop, farmers get more food from the same area of land than if only potatoes were grown. With the added value of the edible legume grains, intercropping can increase the value of the harvest by the equivalent of three to fifteen tons of potatoes per hectare, if the right legume species is used for the field’s agroecological zone. Legume intercropping can increase the net returns in the highlands by up to USD 4,888 per hectare (Figure 2, green hills) and by up to USD 5,880 per hectare in the lower midlands (Figure 2, orange hills).

[/cs_text][cs_element_image _id=”12″ ][/cs_element_layout_column][/cs_element_layout_row][cs_element_layout_row _id=”13″ ][cs_element_layout_column _id=”14″ ][cs_text]

So, choosing the right legume depends on the altitude, maturity dates and the soil of each area. Figuring out the right planting distances for potatoes and legumes, as well as staggering the planting dates, can enhance soil fertility and modify the microclimate of the plants with little loss of yield. One of the most promising legumes for the drier midlands is lablab (or dolichos), a high-yielding crop that produces more biomass than the others tested. Vetch, lupin, lima bean and lucerne (or alfalfa) also showed great potential to control soil erosion in the highlands and to improve potato yields.

Total plant growth in an intercropped plot is higher than the biomass produced by potatoes alone. The legume roots also go deeper, as much as a meter, versus just 30 centimeters or so for potatoes. Long roots allow legumes to lift moisture from deeper underground. Planting legumes also increases the nitrogen content in the soil which might help reduce the need for nitrogen fertilizer.

After harvest, the crop stubble is incorporated back into the earth, returning phosphorous, nitrogen and other nutrients to the soil. This also increases organic matter and makes the soil more porous (so it will hold more water and allow roots to grow more easily).

[/cs_text][cs_element_icon _id=”16″ ][cs_element_quote _id=”17″ ][cs_element_icon _id=”18″ ][/cs_element_layout_column][/cs_element_layout_row][cs_element_layout_row _id=”19″ ][cs_element_layout_column _id=”20″ ][cs_text]

Potato-legume intercropping can fulfill important roles in helping smallholder farmers adapt to climate change by controlling soil erosion in the highlands. Intercropping also keeps soil cooler, while retaining moisture and nutrients in the drier, lower midlands. Legume intercropping is ideal for smallholders, as the innovation requires little investment. With a handful of legume seed, and an eye to the future, farmers can try intercropping and sustain it.

[/cs_text][/cs_element_layout_column][/cs_element_layout_row][/cs_element_section][cs_section bg_color=”transparent” parallax=”false” separator_top_type=”none” separator_top_height=”50px” separator_top_inset=”0px” separator_top_angle_point=”50″ separator_bottom_type=”none” separator_bottom_height=”50px” separator_bottom_inset=”0px” separator_bottom_angle_point=”50″ _label=”Section 2″ style=”margin: 0px;padding: 30px 0px 45px;background-size: 100%;background-position: top;”][cs_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” style=”margin: 0px auto;padding: 0px;”][cs_column fade=”false” fade_animation=”in” fade_animation_offset=”45px” fade_duration=”750″ type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0 0px 0px;”][x_share title=”SHARE THIS” share_title=”” facebook=”true” twitter=”true” google_plus=”false” linkedin=”true” pinterest=”false” reddit=”false” email=”true” email_subject=””][/cs_column][/cs_row][/cs_section][/cs_content][cs_content_seo]Potatoes and legumes: better together

Legumes can be intercropped with potatoes to help manage soil erosion. In addition, a legume intercrop boosts the overall productivity of the land, while helping to improve soil moisture and soil fertility.

In East Africa, potatoes are an important crop for consumers and for highland farmers, helping to improve the livelihoods of rural families. Potato fields usually depend on intensive tillage, contributing to erosion on fragile soils, particularly on slopes. Farmers are also starting to plant potatoes at somewhat lower altitudes where heat and drought are problems. Here, low yields and erosion are exacerbated by the warmer, dryer climate, and by more erratic rainfall. Yet with a growing population, people need to use land more intensively and in a sustainable manner.

A CIP team is developing a practical solution to improve soil conservation in the East African highlands by intercropping potatoes with legumes. The legumes grow a thick canopy of leaves, which covers the soil, shading and cooling it, thus increasing soil moisture (see Figure 1). This helps the potato crop in warmer areas. When cropped on steeper land, the thick canopy reduces damage from hard rainfall and protects the soil from erosion caused by runoff. And by adding a legume crop, farmers get more food from the same area of land than if only potatoes were grown. With the added value of the edible legume grains, intercropping can increase the value of the harvest by the equivalent of three to fifteen tons of potatoes per hectare, if the right legume species is used for the field’s agroecological zone. Legume intercropping can increase the net returns in the highlands by up to USD 4,888 per hectare (Figure 2, green hills) and by up to USD 5,880 per hectare in the lower midlands (Figure 2, orange hills).

So, choosing the right legume depends on the altitude, maturity dates and the soil of each area. Figuring out the right planting distances for potatoes and legumes, as well as staggering the planting dates, can enhance soil fertility and modify the microclimate of the plants with little loss of yield. One of the most promising legumes for the drier midlands is lablab (or dolichos), a high-yielding crop that produces more biomass than the others tested. Vetch, lupin, lima bean and lucerne (or alfalfa) also showed great potential to control soil erosion in the highlands and to improve potato yields.

Total plant growth in an intercropped plot is higher than the biomass produced by potatoes alone. The legume roots also go deeper, as much as a meter, versus just 30 centimeters or so for potatoes. Long roots allow legumes to lift moisture from deeper underground. Planting legumes also increases the nitrogen content in the soil which might help reduce the need for nitrogen fertilizer.

After harvest, the crop stubble is incorporated back into the earth, returning phosphorous, nitrogen and other nutrients to the soil. This also increases organic matter and makes the soil more porous (so it will hold more water and allow roots to grow more easily).

Legume intercropping is a wise investment in the future, says Shadrack Nyawade, one of the researchers on the team. Every year, intercropping builds the soil a little more, while monocropping degrades it.

Potato-legume intercropping can fulfill important roles in helping smallholder farmers adapt to climate change by controlling soil erosion in the highlands. Intercropping also keeps soil cooler, while retaining moisture and nutrients in the drier, lower midlands. Legume intercropping is ideal for smallholders, as the innovation requires little investment. With a handful of legume seed, and an eye to the future, farmers can try intercropping and sustain it.

SHARE THIS

[/cs_content_seo]

[/cs_content_seo]